Mark Simmonds

In September 2012, our 16-year-old daughter, Emily, entered sixth form at Aylesbury High School to begin her A-Levels. She was level-headed, sensible and talented at many things. A month or so later, my wife, Mel, approached me with a slightly worried look and said, ‘We need to talk about Em.’ She had been restricting her food and had developed an eating disorder. Anorexia Nervosa.

Mel and I would soon discover what a brutal, relentless, and unforgiving enemy we were up against. In between 2012 and 2018, we lurched from one nightmare to the next: Emily was unable to take her A-levels, spent a year in three different eating disorder clinics, self-harmed, threatened suicide and suffered from severe depression and anxiety. Her weight dropped to 70 pounds, and at her lowest point she had a tube inserted into her nose to give her the nutrition she needed to stay alive.

When Mel and I look back at this time of our lives, we identify four key lessons we learned as carers:

- Get help quickly. Anorexia is a mental illness. It’s complicated and impossible to predict. Unlike breaking a leg, there is not a straightforward path towards recovery. So, look for expert support as soon as you suspect that something might be amiss. The longer you leave things, the longer anorexia has to dig its claws deep into your loved one.

- Learn to speak “Irrational”. “If you don’t eat enough food, your bones will weaken, and you will develop osteoporosis.” “If you stop eating, your periods will stop, and this means that you risk not being able to have children.” Very rational lines of argument, but to somebody suffering from severe anorexia, you might as well be talking Swahili. Listening, empathising, loving, holding, providing hope and painting a picture of what life will be like again one day soon. It’s the language of emotion that an anorexic understands.

- Be a Dolphin not a Rhino. Janet Treasure, Chief Medical Officer at Beat (the UK’s leading charity for people suffering from eating disorders) developed a powerful metaphor to help parents and carers behave more effectively with anorexics. It is based around different animals. The Rhino uses brute force, logic and strong arguments to convince the sufferer their way is the correct way. The Ostrich lives in denial because they find it too hard to cope with what is going on in front of them. The Dolphin uses just enough caring and control to nudge the sufferer towards recovery. And the St. Bernard shows compassion and consistency, remaining unflappable and never leaving your side.

- Show resilience. Viktor Emil Frankl was a Holocaust survivor who lived to the age of 92. The book for which he is famous, “Man’s Search for Meaning”, provides a graphic account of how he managed to survive the horrors of the Holocaust by finding a way of relating to his experiences. What he noticed was that it was the prisoners who were prepared to comfort those in greater need who survived longest. They developed resilience. Mel and I were no Viktor Frankl. But we learned all about resilience. And so did Emily.

Emily survived and is now thriving, living and working in London, aged 23. 20% of people who develop anorexia don’t make it.

As with any mental illness, there cannot be just one route to the promised land of recovery. There is no silver bullet. But the role of the carer, the parents in particular, is always going to be pivotal.

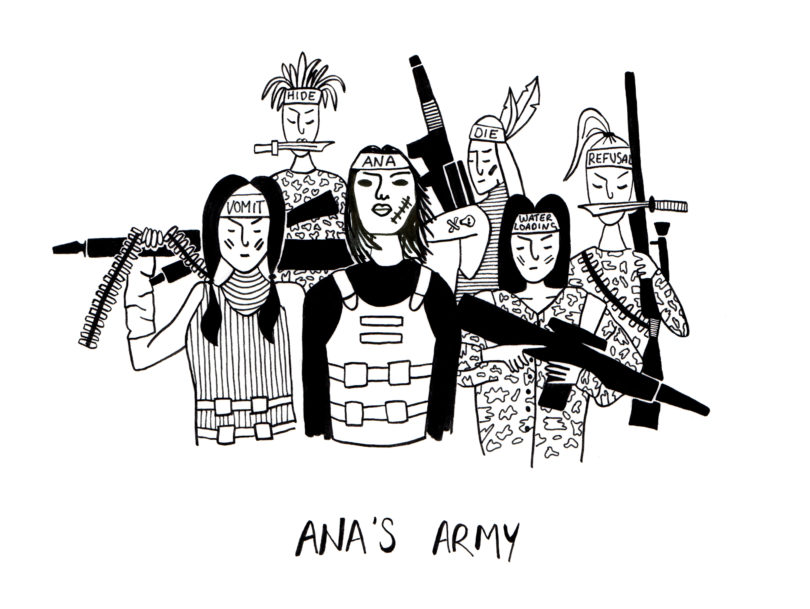

- Mark Simmonds has published his first book, Breakdown and Repair. It provides a full account of his daughter’s struggle against anorexia. It also talks candidly about his own experiences with mental ill health. You can also follow Mark on Instagram @mentalhealthmark. Illustration by Lucy Streule.

Leave a comment!